February 12, 2026 | Occipital Neuralgia

4 minute read

What Happens to a Nerve Under Long-Term Compression?

As I’ve written previously, the occipital nerves can be compressed by a variety of surrounding structures—muscle, fascia, scar tissue, or even nearby blood vessels such as the occipital artery. Patients often understand that compression can cause pain. A more interesting question is: What actually happens to the nerve itself when that pressure persists? In other words, how does simple mechanical compression turn into chronic nerve dysfunction and pain?

Let’s walk through it.

First, a quick framework

Nerves are living, dynamic tissues. They don’t simply transmit signals like wires. They rely on:

- intact insulation (myelin)

- healthy blood supply

- and adequate space to glide and function normally

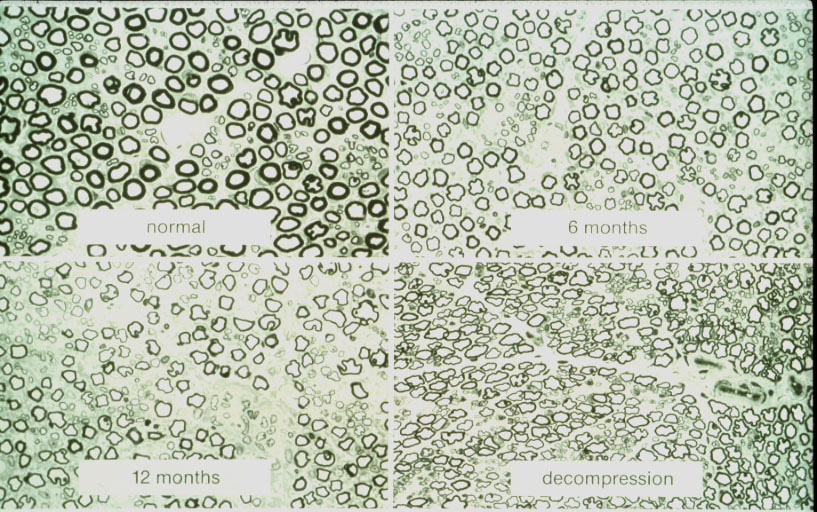

When a nerve is stretched, injured, or compressed—whether from surgery, trauma like whiplash, or tight anatomical structures—its biology begins to change. And those changes are measurable. In the mid-1990s, peripheral nerve researchers studied this directly using a primate model of carpal tunnel syndrome. They intentionally compressed the median nerve for months, performed biopsies over time, and then examined what happened after surgical decompression (see image below).

What they found was consistent and instructive.

Normal nerve (upper left panel):

Healthy nerves are packed with axons (nerve fibers), each surrounded by thick myelin—the insulation that allows electrical signals to travel quickly and efficiently (black rings).

After months of compression, there is thinning of the myelin sheath. (upper right panel):

When insulation deteriorates (thinner black rings), signal transmission slows. Clinically, this can show up as intermittent numbness or tingling. On nerve testing, conduction speeds slow down.

After prolonged compression (lower left panel):

If pressure continues, damage progresses:

- further myelin loss (even thinner rings)

- fewer functioning nerve fibers (fewer rings)

- reduced signal strength

At this stage, symptoms often become constant rather than intermittent. Numbness may persist. Pain may worsen. Electrical studies show weaker signals because fewer fibers remain intact.

After decompression (lower right panel):

When the pressure is relieved, nerves can recover—but not perfectly. Axons can regenerate, and function improves. However, myelin thickness may never completely return to baseline. In short: recovery is possible, but may be incomplete, and time matters.

Why this matters for occipital neuralgia

You might ask: What does the wrist have to do with the back of the head? The answer is: biologically, everything. Peripheral nerves behave the same way throughout the body. Whether the nerve is the median nerve at the wrist, the sciatic nerve in the leg, or the greater occipital nerve in the scalp…prolonged mechanical compression produces the same cascade:

- slowed conduction

- structural deterioration

- fiber loss

- chronic dysfunction

We don’t need separate studies for every nerve to understand this principle. The physiology is universal. The practical takeaway: If a nerve is mechanically compressed, medications alone usually can’t solve the problem. Drugs may temporarily reduce inflammation or blunt pain signals.

But they don’t remove pressure. And as long as pressure persists, the underlying injury continues. Relieving the compression, in appropriate and carefully selected patients is often the only way to address the root cause rather than just the symptoms. Timing also matters.

The earlier a chronically compressed nerve is decompressed, the greater the potential for meaningful recovery. The longer it remains compressed, the less reversible the damage may become.

What we still don’t know

Two questions patients often ask are:

- How much pressure is too much?

- How long is too long?

Unfortunately, there aren’t precise thresholds. Every nerve and every patient is different. What we do know is that chronic compression is not benign—and for people living with persistent occipital neuralgia, waiting indefinitely rarely improves the situation. Bottom line: Nerves don’t simply “hurt for no reason.” Prolonged compression causes real, structural, biological changes. And while nerves can heal, they are mortal. Addressing the source of compression—rather than just treating symptoms—often gives the best chance for durable relief.